Sunday, January 10, 2021

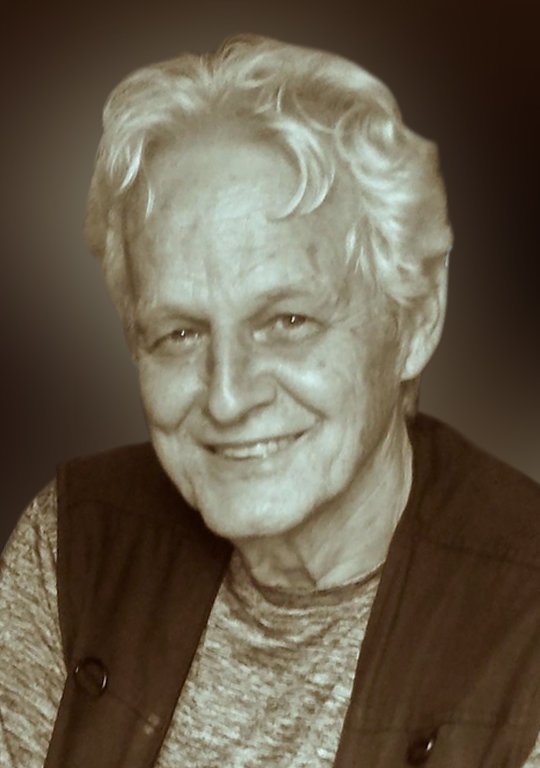

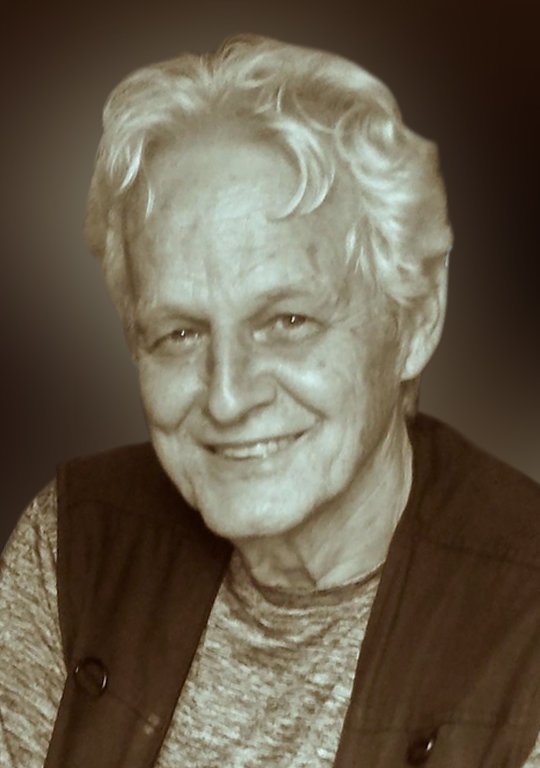

I have yet to figure out exactly what I want to say about my dad, and sadly due to COVID, most of you will not be at his funeral. However, I wrote this a few minutes ago, and I hope it gives everyone a sense of the incredible person he was to all of us who were lucky enough to call him family, friend, colleague, or teacher ❤

I am still in no shape to describe my dad or to adequately memorialize him. There are many words that have been used to describe him over these past few days—kind, giving, a true Renaissance man, loyal, humorous, always ready to help someone in need, a brilliant mind, skilled teacher, deeply proud of his family, an amazing husband to my mom, and the list goes on.

All of this is very true. He is the guy who published an article entitled “Re-Proofing the Zero Part of Speech” in Hamlet” one month and a few months later published “Tupac’s Quest for Black Jesus: God as Deadbeat Dad and Afeni, the Migdala.” To call his scholarly interests diverse would be a tremendous understatement.

My dad didn’t publish because he needed to for his employment; he secured the rank of professor many years ago. He published because his mind never stopped processing the texts around him—whether those texts be a well-known poem such as Poe’s The Raven or more, shall we say, popular texts such as MTV’s documentary series Catfish. He woke up before dawn most days to write and could speak for hours about his projects; this writing invigorated him, and despite my best efforts to not get trapped into caring about what he was talking about, he would inevitably draw me in.

He brought this same level of excitement to his classroom. My dad did not teach the subjects that many students would necessarily automatically enjoy. Early Modernist and Long-18th Century courses are intellectually challenging, as students grapple with writing styles and philosophies that they likely have not seen very much of previously. However, with his quiet voice, quick smile, and true passion for the material, he could make the most challenging of material interesting for his students.

I worry that the Little Caesar’s at 6 Mile & Livernois might struggle to stay in business now that my father is no longer around. He made frequent visits to that location, as bringing pizza to his students was an extremely common occurrence in his classroom. Teaching his students, helping them develop their own academic pursuits, and getting to know them as individuals was truly one of the greatest joys in my father’s life. He always told me that he had no plans to retire because he still looked forward to going to work everyday, visiting with his colleagues and the whole College of Liberal Arts crew, and teaching his students.

It is hard to imagine walking into the Briggs building ever again, as I will always be waiting for my dad to turn around a corner. I grew up on the McNichols’ campus. I remember waiting for him to finish teaching one evening class and looking up from my coloring book, only to loudly say “Oh, Daddy, you’re so crazy.” Needless to say, that story made it through campus quite quickly.

In all seriousness, though, I learned a great deal from following my dad around UDM for all of those years. He taught me the art of close reading and how to take those small observations and turn them into research projects. Most importantly, though, he showed me what it meant to be a great teacher. Knowing what you’re talking about is only a small piece of the puzzle; the larger piece is recognizing each student and genuinely showing interest in their work. Michael Barry, a close friend and colleague of my dad, recently shared with me that my dad told him early on in his teaching career to “be yourself” with your students.

As I think of stories from my dad’s teaching career that include jumping rope through the hallways of Briggs, playing Office episodes in class to explain some concept regarding irony, and joking to the basketball players in his class that he still had four years of college eligibility if they were looking for a new teammate, it is not at all surprising that this is the advice he would offer a new teacher. My dad walked into every room with a quiet humility and grace. Realistically, I will never be the teacher my dad was; however, when my office hours run long because a student is struggling, or I spend a ridiculously long time perfecting a student’s recommendation letter, I know that these are the pedagogical behaviors and values that I learned from him.

So far, I’ve described my dad as having a tremendous humility, which he did. However, that humility did not extend into how he would speak of my brother or me. He often tells how he knew my brother would become a poet ever since he was a little guy and told him that the “sky of his mouth” was hurting. Whenever my brother had a poetry reading or played a gig with the Codgers, you would not find my dad calmly siting and listening. He would instead be to the side of the stage proudly watching him perform. While quiet and humble, he was also the ultimate stage parent, and his pride in Johnny was truly palpable to anyone who might happen to be in the room.

I was the youngest in my family, and in my dad’s eyes, could do no wrong (Clearly, he was correct in that assessment.). In my early years, I think I viewed most of the world from 7 1/2 feet off the ground, as he would cart me around on his shoulders through Warrendale, the Detroit neighborhood we called home the first eight years of my life. We made our daily trek along Warren Avenue to Dawn's Donuts and then to the party store across the street where I could always convince him to purchase me an ice cream or whatever else I had on my mind that day.

While I eventually grew too tall to be carried along on my father’s shoulders, he never actually stopped trying to carry my metaphorical burdens throughout life. When I would become stumped while writing a paper, he would sit there and talk through ideas with me well into the night. When my dog rolled in something disgusting and I could not stop dry-heaving long enough to throw her into the tub, he would show up and save me from these miserable life moments.

Unfortunately, on the night of January 7th, the day I’ve never wanted to see occurred when my sister-in-law knocked on my door and told me that he was gone. As we pulled up to my parents’ house, my eyes turned to the garage where my dad and I spent countless hours shooting baskets, and I collapsed to the ground in tears there, just wanting to disappear and not have to face what happened.

In this moment, I had this sinking thought that I could not get through the world without him by my side. I am an anxious mess of a human in most cases, and he was always there to help pull me together when I needed him. He taught me how to have compassion and grace for others, how to fight like hell for the causes that you believe in, and to always, no matter the consequences, be there for everyone around you. As the phone calls, visits, and text messages started to filter in over the past several days, I realized that I unconsciously have chosen to surround myself with people who have the same ethos that my father had, loyal to a fault, ready to drop everything for those they care about, and a deep sense of social justice. Of all the gifts he has left me, this is the greatest of all.